Today is the turn of GEA exec member Sharon Lamb to share her experience of The Women’s March 2017. Sharon marched in Washington and her post discusses identity politics and why we ALL need to come together, now more than ever, to challenge sexism and inequalities.

You can also read Jessica Ringrose’s and Victoria Shouwnumi’s posts on The Women’s March

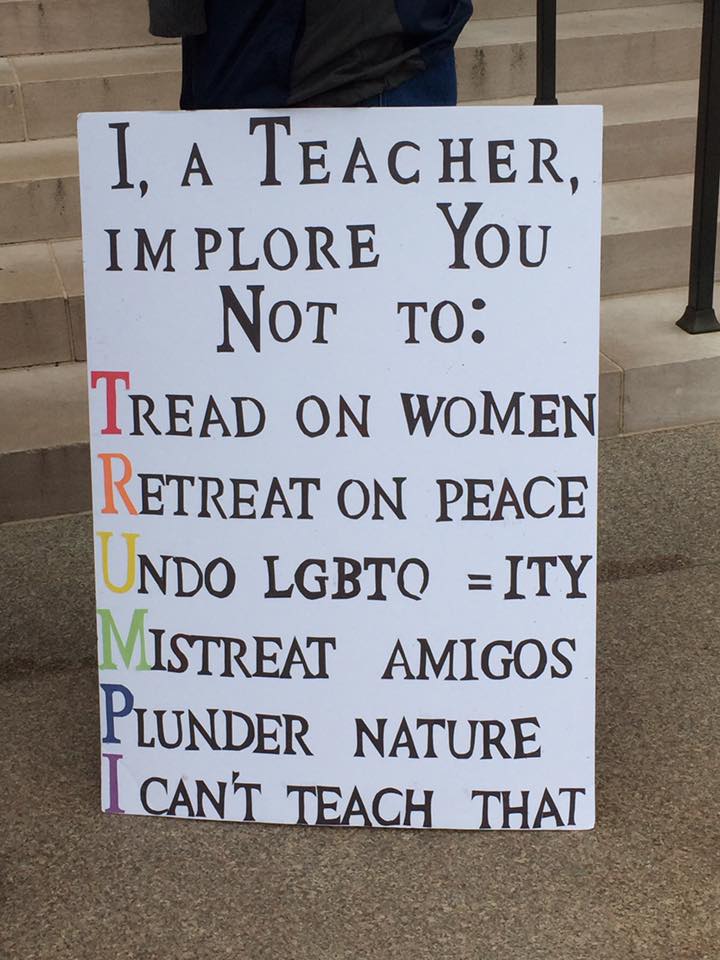

The Women’s March on Washington, which began as the Million Women March and ended as a 3 million women march in the US with many more around the globe, was a revelation on how women can unify. I marched in DC and was truly amazed at the coming together of a number of issues, demands, and approaches all co-existing for a moment without contradiction: Viva La Vulva; Black Lives Matter; Climate Change is Real; My Body My Choice; Say it loud and say it clear, Immigrants are welcome here; Sí se puede – yes we can; What does democracy look like? This is what democracy looks like; Build bridges not walls; Intersectional feminism; My body my choice my country my voice; Immigrants are who make America great; Oh America, what have you done?; Friends of Dorothy Support Women; Viva la Vagina; Do Justice, Love, Mercy March Proudly; Not the church and not the state, women will decide their fate; Keep your laws off my body; Women don’t back down; This pussy grabs back/has claws; If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention; Not on our watch; and Are you fucking kidding me? A multitude of chants. One voice.

Not so true of the days and weeks leading up to the march. Any sniff of lack of unity among women was sent around by bloggers, journalists, and tweeters as one more sign that women can’t get along and also of the continuation of demoralizing identity politics. White women did not reflect on their privilege enough. Black women had to fight for visibility. Brown women and Native American women and Asian-American women’s voices weren’t heard very often because there was no nifty opposition of pro/con, yes/no, us/them that the media loves to present as Black and White. And then everyone forgot about class, the biggest divide, even after ignoring socioeconomic class was what cost democrats the election.

There were tensions for sure. A coalition that size can’t avoid them. But as usual, the divisions and not the effort to engage a diversity of voices made the news. Women bickering is almost too great a story for the media to ignore. The NY Times couldn’t resist a front page article on a Facebook post by a Black 27-year-old activist from Brooklyn who made one 50-year-old White woman from South Carolina feel “uncomfortable” marching.

Ms. Willis, a 50-year-old wedding minister from South Carolina, had looked forward to taking her daughters to the march. Then she read a post on the Facebook page for the march that made her feel unwelcome because she is white.

The post, written by a black activist from Brooklyn who is a march volunteer, advised “white allies” to listen more and talk less. It also chided those who, it said, were only now waking up to racism because of the election.

“You don’t just get to join because now you’re scared, too,” read the post. “I was born scared.”

Stung by the tone, Ms. Willis canceled her trip.

The title of the article was “Women’s March on Washington Opens Contentious Dialogues about Race.” Opens? I have to ask the New York Times, where’ve you been? Why is this 50-year-old minister’s hurt feelings suddenly newsworth?

It’s true that the first few people who said, “Let’s have a march” were White women. But when they faced justifiable criticism, they were responsive to these critiques to such an extent that one initial critic later called the platform truly “intersectional.” But haters gonna hate and dividers gonna divide and the media gotta sell ads.

Next came the news that pro-lifers were uninvited. And when I tried to find where and how that happened, I discovered that they decided themselves not to march but not that they were uninvited. I did find that their “partnership status” in the planning of the march was revoked. But I’ll betcha anything that there were pro-lifers marching out there who also cared about immigrants, police brutality, and climate change. Most likely some right wing pro-life organization made public that they’re not going to march as a way to get a little press. Trump has shown the world how to get publicity and the media doesn’t seem to change on that score.

There were also tweets, posts, and blog pieces that were heartfelt about how some individuals felt not included. These personal “why I won’t march” stories, (like one by a former student of mine who complained on Facebook that the very women who mistreated her once were now on Facebook ironically promoting women’s rights), describe real hurt for sure. But when these opposing voices are promoted to front-page news it becomes part of the fodder that men have always used to divide and conquer when they say that women just can’t get along.

Yet during the march, we were, as one sign put it: “indivisible.” And that’s where we need to remain in spite of the fact we don’t always agree and sometimes hurt each other’s feelings. Really. How are you going to get half the world to agree on anything when they can’t even agree on climate change?

I didn’t supporteverything on the platform, nor every poster or slogan or chant. I marched, shouted when the feeling was heartfelt, and was quiet when I didn’t agree. For example, I didn’t like signs with a picture of a pile of poop on Trump’s face. They seemed slightly contradictory to the slogan, “When they go low, we go high.” But I was there and not chastising my sisters, because, well, the overarching message that Trump is dangerous and women’s rights everywhere are at risk is just too important to be derailed by my discomfort around a pile of poop.

I am personally done with the idea that “the personal is political.” In a neoliberal society, where personal choice is elevated, and individual rights are reduced to the right to shop for schools and carry assault rifles, the 2nd wave slogan that the personal is political has a different meaning. It no longer means: look at what’s personally happened to you and connect it to a political movement, to politics, to other women. Today we stop at what is personal and bring it to voice as if that and only that is political. And we see other people unidimensionally as representing only one voice, one race, always acting out of self-interest or interest for “one’s own kind.” And this interferes with the ability to see an ally as an ally when she comes forward.

The personal is political is not only used to describe the individual coming to voice. It morphed into identity politics, which is unashamedly a politics of self-interest, even if it is well-deserved self-interest, as in “If I am not for myself, then…” Next came interesectionality, which is a concept that seems to me to be supported only when it means the adding on of oppressions and not used very frequently when intersecting privilege undermines any voice of oppression. As with identity politics, the voice of interesectionality continues to honor personal feelings and story telling, and the stories that make the rounds are those that mark the greatest victimization where multiple identities have been oppressed. It encourages individuals to look at how you yourself have been harmed in so many ways rather than how others have been harmed. Personal story trumps history, trumps facts, trumps context. (Someone stop me from using that word ever again!)

There is a genre that I and others noted in the 1990s in popular writing about the sexual abuse or rape victim, a story of stigmatization and never-ending trauma, a genre that undermined the empowerment of victims because it required them to call themselves survivors and never recover. Today many race and ethnicity stories follow this same genre with the tag ending of “And still I rise.” I want to be clear that I do believe that some rape victims as well as victims of racism and racial violence are traumatized for life. But how do these trauma stories work? What do they do? What purpose do they serve? And quite separate from their intent, how are they taken up into an ideology of female weakness, the need to protect rather than empower, and the suppression of voices of unity and strength. Voices of unity? How about “And yet we rise.”

Finding one’s voice. Becoming a subject. Writing from first person perspective. This is encouraged in schools with endless self-reflection papers. I assign them. I read them. And they are earnest and feel to the writer as if her self-discovery is original but, when you read a number of these, you begin to see that an individual’s coming to voice often reflects ideologies and movements in history sometimes quite unknown to the author. The lens is brought to bear so inwardly or so close to oneself and one’s own identity that it is suffocating and the outcome is that we believe one can only speak for oneself and one’s own identity or identities. We teach that you have a voice and that is the voice to cultivate. Precious voice. A jewel. Do not be silenced. It’s a lesson on individualism rather than unity and instead of similarity.

That is the Western individualized identity politics mindset that we need to get out of in order to march together, the mindset we did get out of if only for a day. We didn’t march to express ourselves. Well, maybe some of us did. But in spite of that very Western urge to make one’s voice be heard, we marched for other people, and now, hopefully, we are prepared to fight for them, even if politics won’t allow us to speak for them.

The women’s march was a coming together of people with diverse interests and diverse views. For the last time I hope I will have to identify myself as a White cisgender heterosexually inclined, Jewish but not religious woman who grew up in the lower class but whose family moved to the middle class by the time I was 16, who was the only White high school student who took the African American history course, who grew up with a grandmother immigrant in the household, and who is the mother of two young men and the grandmother of a disabled grandson. With Trump as president, some groups’ rights are more at stake than other groups’ rights. For sure. And some people need to be a lot more scared than I am right now. But when I say I’m scared. I don’t mean I’m scared for myself. (Some critic of the march chastised a White woman saying something like, you’re scared? Well I’ve been scared all my life.) When I say I’m scared, I mean I’m scared for you. And you. And you. And the earth. And the future. So if we need to be divided, let’s divide the world the way Michael Che did on Saturday Night Live – there are reasonable people, and then there are dicks. We have a dick in the White House. Let’s bring reasonable people together to fight for other people, reasonable or not. The Women’s March is just the start.