A few months back a youth work colleague voiced concern about the young women she works with listening to a rising new female rapper, Nicki Minaj. She felt that the lyrics and the image were over-sexualised and liable to provide a potentially poor role model for the young people in the youth project with whom she worked. This also followed a YouTube sensation of two very small British girls, Sophie-Grace and Rosie belting out Minaj’s tune ‘SuperBass’ which was proudly recorded by their mothers. The YouTube hit enabled the young girls to have their precocious 15 minutes of fame as they sat next to US chat show host, Ellen DeGeneres and performed with their idol, Nicki on the Ellen talk show.

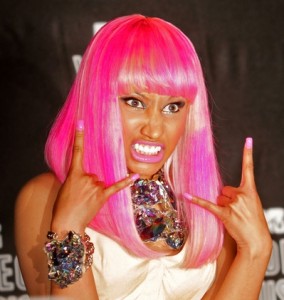

Other youth workers mentioned Nicki as a favourite for many teen girls. Friends of mine also posted comments on Facebook drawing attention to Minaj’s risqué videos, and in the morning rush hour, I noticed pupils played her music through their smartphones on the back of the bus on the way to school. Following the pick and mix stylings of Lady Gaga and the ever- changing darling of 1980s postmodern imagery of pre-Sex Madonna, Nicki’s image seemed to be everywhere. I saw her on the tube, on huge billboards at the side of the road complete with blonde wig and white face. On her videos she squeakily voices the mantra “She’s a stupid ho”, repeating the number of artists from Pink onwards who choose to pour scorn on other women in their lyrics.

This summer I attended the first of Nicki’s solo concerts in London. It was to prove memorable. The long queue to get in snaked about ¼ mile down the road. I walked past groups of young women dressed up as mini versions of Nicki, with pink and blonde wigs, batty riders and gig T shirts. Unlike many other events that I have attended- which are largely male preserves- the average fan for this concert was 14, female and came with a large group of friends. The tickets had sold out after 8 minutes for this first UK show. Fans had camped for hours out in front of the venue steps in the mixed weather of an English summer. Upon approaching the venue, the audience had to step over the detritus of the all day camping queue. It resembled a teenage bedroom, with Hello Kitty blankets, empty cupcake wrappers, copies of Heat magazine, bottles of soda, chicken wings and pink flip flops being amongst the discarded items.

In the theatre the girls waited breathlessly, screaming every time the curtain twitched and they thought Nicki might be revealed. When she did – a mere 30 minutes late- the crowd held their smartphones aloft and watched Nicki through the view finders, recording the moment to be later uploaded on Youtube. The girls behind me watched the football Euro quarterfinals (Italy vs. England) on their Blackberry. One eye on the score, one eye on the stage- cheering on England and afraid they would miss the winning goal or a highlight in Nicki’s performance.

As Nicki sang, she would occasionally pause to let the crowd sing her lyrics back to her. I looked on as around 8000 teen girls punched their arms in the air and sang the rather explicit lyrics to the track, ’Come on a Cone’ with the chorus of “Put my dick in your face… Put my dick in your face….”

I was puzzled. Here were these young women smiling and singing about their imaginary phalluses – are these the ‘phallic girls’ of Angela McRobbie’s writing? Minaj facilitates this phallucism via her schizoid meld of alter egos, genders and imagined bodies where we can be invited to variously ‘kiss my disney’ or ‘suck her dick’. Such assertions of the imaginary (female) phallus are to take on an act of triumphalism. The track, Come on a Cone is about a narrative of affirmation and confidence, and the ‘obscene’ chorus with its sexual threat wrestles the phallus from the boys, and imagines a space where young women wield phallic power to demonstrate their own virility and castigate others. It is a lyric written as another male rapper would but sung as an R&B style chorus, which is arguably further subverted as schoolgirls from Milton Keynes, Cambridge and Southend made the chorus their own anthem in a moment of subversive gender-play and togetherness, their tuneful voices in unison.

“Hello my little Barbies!’ Nicki greeted the crowd. “You are all my Barbie’s now!” The screams increased in intensity and pitch. Nicki Minaj was suddenly greeted as if a boy band member – she hitched up her tutu and showed off her behind.  More screams of delight erupted from the teen girl crowd with Nicki cast as lust object, as pop star, as best friend, as Barbie.

More screams of delight erupted from the teen girl crowd with Nicki cast as lust object, as pop star, as best friend, as Barbie.

At times, Nicki left the stage for up to 5 minutes for a change of outfit, as the DJ played tracks of her songs and the girls in the crowd sang and danced along, pausing only to take pictures of themselves embracing. Nicki would return singing a new genre with a new frock. She moved during the evening from Europop to Hip Hop to R&B Ballad. Each style being complimented by a new look and wig, partially reminiscent of a branch of the Early Learning Centre’s dressing up box- the fairy style tutu, the princess white netting, if not, the more ‘adult’ back basque and net skirt for her final mix tape, Hip Hop Style.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, as part of her act, Nicki has a range of alter-egos from the angry tirades of her British gay male persona, Roman Zolanski, to his mother, Martha Zolanski, ‘Harajuku Barbie,’ and ‘Nicki Minaj’. The use of alter-egos in rap is far from new- Eminem’s Slim Shady is a case in point. The alter-egos allow Nicki the space to hold up a mirror and articulate a wider range of expressions than was perhaps open to earlier rappers such as Lil Kim.

The female rapper, Lil Kim, for example, often seemed to be ‘one for the boys’. Conversely, Nicki, often seems to be one for a range of younger and older women. Minaj’s sex appeal and sculpted curves appear cartoonish, rather than simply ‘sexy’, in common with other contemporary young female singers such as Katy Perry’s breast aerosol cream squirting antics on the video for California Girls, were alluring and childish. Indeed, Minaj’s Barbie Pink appeals to much younger girls than were present at the gig -as reflected by tweenies Sophie and Rosie’s YouTube adulation. At the same time, Nicki in interviews and in her rap lyrics states she wants to be the female rapper version of Lil Wayne, and this means her lyrics give her the edge and sassiness as previously embodied by Lil Kim, but with potentially an appropriation of the harder edge and lyrics achieved by male rappers. Indeed one of her public spats was with Lil Kim – whose act she has arguably borrowed some of her iconography, and the rage filled lyrics of “Stupid Ho” aim to dismiss and goad the older (and arguably less successful) Lil Kim about Nicki’s recent success.

It is in the bridging of genre, style and audience that make Nicki arguably stand out from the pack of other popular female singer/rappers. Her rapping style metamorphasises across and within tracks. Her identities are multiple and unstable. She changes gender, ‘race’, age and sexuality between them. Within the sex-gender play and generational ‘drag’ within her tracks and interviews. Internet rumours abound about her perceived sexuality.

The pallet of alter-egos thus enable Nicki to embrace different audiences for her music, and express multiple and contradictory aspects of femininity. Indeed her appropriation of Barbie imagery has recently been immortalized in plastic by Mattel in the form of the Nicki Minaj Barbie. This conscious transition of pop stars such as Nicki and Katy Perry to become real life dolls is an active comment on the artificiality of fame and image. As noted in a recent blog by Sarah Todd, the ongoing affinity with Black rap artists and Barbie date back to Lil Kim rapping about being the Black Barbie.

Todd writes: ‘Given this history, the lure of Barbie for black female rappers might seem to reflect an internalization of white beauty standards. … By claiming the label of Barbie or black Barbie, rappers like Lil’ Kim and Minaj can signal that they have a mainstream (read: “white-people-approved”) beauty.’

Yet Todd also wants to argue that Minaj’s appropriation is not as simple or as straightforward as a simple taking on of white-mainstream beauty standards. Indeed, Todd’s analysis goes on to explore how the use of Barbie imagery can ally these artists to girls and girl cultures. In addition, the appropriation of Black Barbie imagery by Lil Kim and Minaj also provides a canvas from which to draw attention to their own perfection and artifice, potentially both glorifying and critiquing hypersexualisation simultaneously. Moreover, Barbie provides only one aspect of Minaj’s persona, in that as a female rapper there are few positions that a female rapper might take – for example, shall I actively court male attention or be a tom boy? Yet Todd’s analysis suggests that the use of Barbie forms a girl-friendly space that navigates through these polarized identities. Indeed, for Minaj, Barbie is just  one of a range of personas to be drawn upon and enacted at different points in her repertoire. Her creation of Roman as an angry Gay British guy, creates yet another space to articulate rage, and a positionality that does not purely reflect the norms of fashionable dominant norms of heterofemininity nor uphold the ‘tomboy’ female rap persona.

one of a range of personas to be drawn upon and enacted at different points in her repertoire. Her creation of Roman as an angry Gay British guy, creates yet another space to articulate rage, and a positionality that does not purely reflect the norms of fashionable dominant norms of heterofemininity nor uphold the ‘tomboy’ female rap persona.

Of course, questions remain about the spaces and opportunities for female rappers and performers more broadly, and how consumerism and commodification package contemporary pop stars for the market. Indeed, what sort of icon is Nicki Minaj? And should I as a feminist feel a guilty pleasure for my hours on the internet trying to track down tickets for her UK gigs?

Fin Cullen, Centre for Youth Work Studies, Brunel University.