When I was 13, I took a train to Birmingham with a friend. The train conductor came to inspect our tickets, before handing them back he lifted up our t-shirts and stamped our belly buttons. He returned to the driver’s cabin, laughing.

This and many other memories of bodily intrusions have been on my mind this week as the words ‘me too’ reverberated across social media.

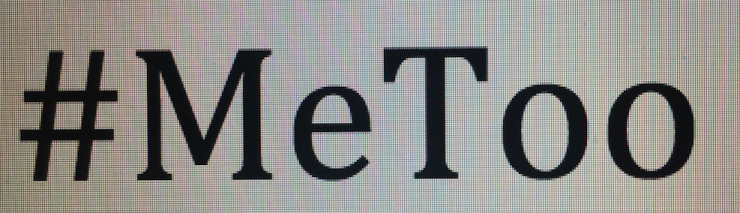

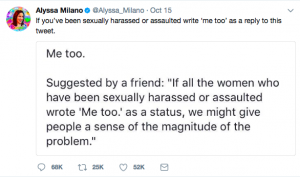

In response to growing reports of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual predation, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted, “Suggested by a friend: If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.” Since Sunday friends, family, colleagues and acquaintances (mostly women and non-binary people) have been sharing their stories of being groped, grabbed, leered at, cornered, flashed, stalked, violated, raped.

Me too. These words have a history.

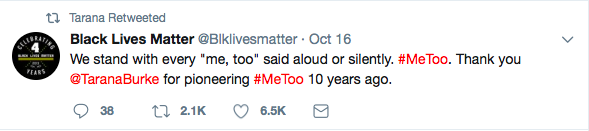

In 2006 Tarana Burke founded the ‘me too’ movement to aid survivors, particularly young women of colour, in communities where sexual assault services were under-resourced or non-existent. In a statement about ‘me too’ Burke told Ebony Magazine, “it was a catchphrase to be used from survivor to survivor to let folks know that they were not alone and that a movement for radical healing was happening and possible.”

In the aftermath of renewed discussions about sexual assault in Hollywood, the words have picked up pace as a feminist hashtag. #MeToo has sparked conversations and connections, opened up wounds, been left unspoken but nevertheless felt and incited anger and frustration.

A growing body of literature documents how feminist hashtags can provide ‘comforting solidarities and connections between strangers’, as well as entry points to wider feminist communities (Keller, Mendes and Ringrose 2016, p. 12; Williams 2015). However, they can also draw upon, and rearticulate, long-standing inequalities within feminist activism (Khoja-Moolji 2015). For example, the initial credit given to Milano rather than Burke for #MeToo perpetuated the diminishment of black women’s experiences and work within feminism (Hill 2017).

Like others (see here, here, here), I questioned what the hashtag was doing and who it was for. I wondered why the onus was on women to reveal their pain and worried about friends who had shared raw experiences. At times it felt blasé to me – ‘of course we’ve all been sexually harassed and/or assaulted, who is this news to?!’ At others I felt angry as close male friends fumbled their attempts to acknowledge the problem – ‘How do you still not get it?!’

Before I had the words to describe how sexism shaped my world, I had many ‘me too’ moments with girl friends. Conversations that, as Sara Ahmed notes, can act as a ‘drip, drip’ and eventually a flood as you connect your experience with the experience of others (Ahmed 2017, p. 30). I have epic friendships built on this ‘releasing of the pressure valve’ (Ahmed 2017, p. 30). Most notably my best friend Tari with whom a friendship began 13 years ago over shared experiences of ‘coming out’: for her as a mixed race woman, for me as a lesbian.

Of course, ‘women may have common situations and experiences, but they are not, in anyway way, the same’ (Braidotti 2011, p. 156).

This week Tari’s #MeToo post drew attention to the fact that the world has never really respected and understood her body as her own. Her rights to bodily autonomy have been impeded not only by the men who’ve assaulted her, but the women and men who have touched her hair without permission or shouted ‘afro!’ at her in the street.

In my #MeToo post I nodded to the fact that my most recent experiences of sexual harassment have been from men on the gay scene (Tari has also experienced this). Men who tickled my crotch as they walked past me or squeezed my boob, acts that both intimidated and made me feel unwelcome in a space that was supposed to be safe.

The phrase ‘Me Too’ works as a refrain, to draw on Deleuze and Guattari’s (1987) concept, a scoring over of the world’s repetitions, that marks and expresses territories (Youngblood Jackson 2016). Its recurrence weaves together communities of solidarity and simultaneously maps the persistence over time of the sexual violence that elicits it. Each utterance is different from the other, branching off and connecting territories; what we call ‘patriarchy’, ‘misogyny’, ‘heteronormativity’, ‘racism’ or ‘white privilege’. These deeply entrenched territories are marked out by repeating forces of domination and control.

Me Too. These two little words channel the enduring felt force of subjugating systems, the ways they minimize and diminish us. Yet, they also exceed these systems. Me Too.

With each repetition, the ‘refrain becomes more and more mobile, going somewhere – destination unknown’ (Youngblood Jackson 2016, p. 20). Bertelson and Murphie (2010, p.145) remind us that refrains are ‘not just closures but openings to possible change’. With this in mind, I want to end by considering how the intensified situation of a feminist hashtag might be put to work in schools. How might we harness the energy of #MeToo in a way that enables young people to safely and creatively challenge gender inequalities and oppressive gender norms?

——————–

Gender Equality Leadership in Schools (GELS)

Hosted by the Gender and Education Association, GELS helps educators and young people raise awareness of and address gender inequalities. One way in which this work is being taken up in schools is through student-led feminist clubs. Hanna Retallack, an intersectional feminist teacher and researcher, notes that these collectives provide vital space for young people to ‘discuss the issues denied to them by the curriculum’, including the ‘intersectional inequalities that lie at the root of sexual violence and harassment, as well as the structural injustices affecting them both personally and politically’ (Retallack 2016, para 7).

AGENDA: A Young People’s Guide to Making Positive Relationships Matter

Calling out sexual and gender inequalities is not without risk. Utilising the powerful potential of creative methods, such as the visual arts, poetry & theatre, can enable young people to make the personal political without revealing too much of themselves. The interactive Welsh tool-kit AGENDA is packed full of inspiring art-activisms that can help young people engage with all too frequently silenced issues. Developed by Professor Emma Renold and young people in Wales, the toolkit has equality, diversity, children’s rights and social justice at its heart.

Do you have thoughts about the pedagogical potential of hashtag feminism in educational institutions? Consider writing us a blog, we’d love to keep this discussion going.

References

Ahmed, S. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bertelson, L. and Murphie, A. 2010. An ethics of everyday infinities and powers: Felix Guattari on Affect and the Refrain. In: Gregg, M. and Seigworth, G. (eds). 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham: Duke University Press.

Braidotti, R. 2011. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. New Yor: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Keller, J., Mendes, K., and Ringrose, J. 2016. Speaking ‘unspeakable things’: documenting digital feminist responses to rape culture. Journal of Gender Studies [Online]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1211511 [Accessed 20 August 2016].

Khoja-Moolji, S. 2015. Becoming an “Intimate Publics”: Exploring the Affective Intensities of Hashtag Feminism. Feminist Media Studies 15(2), pp. 347 – 350.

Williams, S. 2015. Digital Defense: Black feminists resist violence with hashtag activism. Feminist Media Studies 15(2), pp. 341 – 344.

Youngblood Jackson, A. 2016. Potentializing a Deleuzian Refrain. Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 5(4), pp. 20 – 23.