Written by Michele Paule, Oxford Brookes University

Back in the 90s when I was working in a secondary school, a creative young RE teacher painted a mural of heroes onto the wall of a corridor. The only two women on it were a suffragette and Marilyn Monroe. I suggested to him that there should be more women, and that there should be more areas of influence represented than those suggested by suffragettes and sex symbols. “I see your point” he said, ‘’but what’s the use if the girls don’t recognise them?”

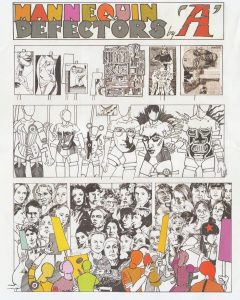

In 2008 the artist Jann Haworth created the comic strip, ‘Mannequin Defectors’ in which mannequins march past a street mural depicting prominent women in the arts and sciences. It was prompted by Haworth’s realisation that she could ‘barely cite thirty’ such women herself.

In 2008 the artist Jann Haworth created the comic strip, ‘Mannequin Defectors’ in which mannequins march past a street mural depicting prominent women in the arts and sciences. It was prompted by Haworth’s realisation that she could ‘barely cite thirty’ such women herself.

I remembered both of these as I began to look at the data for my pilot study that looks into girls’ ideas about leadership and women leaders. ‘Mannequin Defectors’ remains a favourite work, and I hope the RE teacher grew up to create more representative school art, but as a feminist media educator I know that the relationship between representation and audiences is a complex one that goes beyond offering media ‘mirrors’ and assuming effects. The study explores the kinds of ideas about leadership made possible and/or meaningful to girls. It seeks to understand how girls engage with these ideas via figures chosen by themselves, the discourses that surround these figures, and the media and everyday contexts and practices in which such engagements take place.

An absence of visible role models in girlhood is a popularly-cited as a root cause for the shortage of women in decision-making positions in adulthood; initiatives such as Edwina Dunn’s The Female Lead, or the Biographical Dictionary of Swedish Women seek to address this shortage. However valid in themselves though, concerns about the proportion and visibility of women leaders too often translate into ‘role model’ solutions for girls that are based on simplistic ideas of gender-matching. In such solutions the complexities of relationships that young people may have with media figures, and with more locally available role-models, are reduced to a matter of inspiration = imitation; few consider the cultural contexts in which girls encounter these figures, the meanings girls attach to them, and how encounters and meanings are embedded in girls’ everyday lives and media practices.

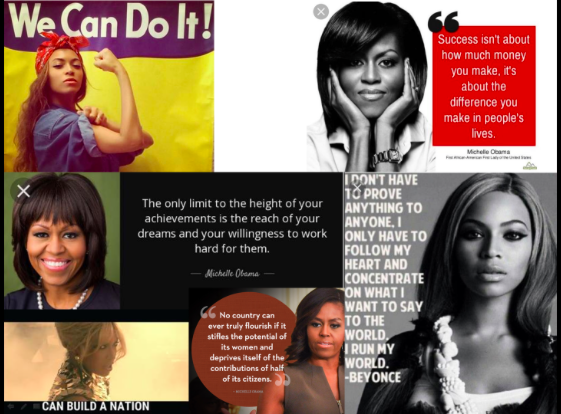

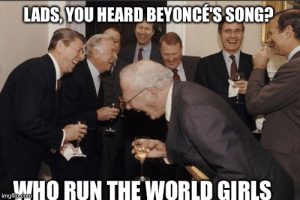

In this post I focus on two leadership figures cited by participants in school interviews and whose images feature frequently as memes in the Facebook group collages created for the project: these are Michelle Obama and Beyoncé.

Global and hyper-local role models

Beyoncé’s had so many like different situations in her life. So from when she was younger she had a lot of horrible experiences. She’s such a public figure that everything that happens in her life, people know about. Participant

Beyoncé’s had so many like different situations in her life. So from when she was younger she had a lot of horrible experiences. She’s such a public figure that everything that happens in her life, people know about. Participant

….

I’d have like my Aunty because like she’s like been through a lot…I look up to her Participant

One of the first things I ask participants to do is to describe a woman leader they admire. Michelle Obama and Beyoncé are the most popular in each group. After these two there is no clear winner, and no British women leaders/politicians are named at this stage. After global figures, girls are as likely to cite women they know, especially their mothers and their teachers, as they are women in the public domain. As they discuss their nominations themes emerge of hardships overcome and personal qualities admired. Participants seem as familiar with the obstacles that Beyoncé has faced as they are with the life stories of their own adult women relations; they quote the aspirational aphorisms of Michelle Obama as they do those of their teachers. This merging of the global celebrity and the hyper-local figure can be understood when one considers ways in which global celebrities have become enmeshed with everyday life, especially through social media. This study will, I hope, contribute to understanding of the role celebrities occupy in the lives of everyday youth, and of what ‘role models’ mean to girls who are neither members of celebrity fandoms nor the subjects of targeted leadership programmes

Merit and influence: leaders and celebrities

Most leaders have like worked hard to become what they are now and a lot of celebrities, a lot of them have also worked hard, but also a lot of them have been born into celebrity. Participant

Most leaders have like worked hard to become what they are now and a lot of celebrities, a lot of them have also worked hard, but also a lot of them have been born into celebrity. Participant

….

A celebrity they like have more influence on younger people like our age group whereas a leader, like you think politics it would be for like older people and for that generation, not ours. Participant

The girls’ nomination of Michelle Obama and Beyoncé as their favourite leadership figures illustrates the blurring of boundaries between celebrity and politics. This blurring is seen not only in the increasing involvement of celebrities in political movements and processes, but in the ways in which politicians construct celebrity identities with what Marshall describes as an ‘affective function’, attracting support around personality and interests rather than policy. This ‘celebritisation’ of politics, with its associations with the ephemeral and the low-brow, was a matter of concern well before the election of Trump, with commentators fearing that

If we don’t take back the celebrity politician system, citizens might well face a political contest between a basket-ball player versus a football player, or a comedian versus rock star, or a movie star versus a television situation comedy star (West and Orman 2002, p.119).

At first glance, the girls’ selections may seem to play into these anxieties. However, to read them in this way is to indulge in simplistic cultural hierarchisation, in which celebrity, and especially the tastes and opinions of the teenaged girl, will always occupy the lowest positions. And while Michelle Obama and Beyoncé could be seen to represent Street’s (2004) distinction between the celebrity politician and the activist celebrity, this divide is not meaningful for the girls. Their discussion focuses instead on the idea of influence – who has it, how they got it, and whether they deserve it. Their distinction between the celebrity and the leader is framed in terms of merit, with the hard-working celebrity earning the status of leader.

The other distinction between the celebrity and the leader is made in terms of generational appeal. Michelle Obama and Beyoncé, the girls feel, do more than ‘sit in a room with a giant bunch of people and argue about taxes and stuff’ and instead are constructed as highly accessible figures who model hard work and the material successes it can bring. InMichelle Obama, participants see qualities of accessibility and everydayness that both sit alongside and are the source of her influence. Her accessibility is partly framed through her status as a Black woman – this is central to their perception of her as a good leader; one participant describes her as ‘someone who came from a background or was born as a minority, can have that opportunity…I think that makes her be a leader’.

The other distinction between the celebrity and the leader is made in terms of generational appeal. Michelle Obama and Beyoncé, the girls feel, do more than ‘sit in a room with a giant bunch of people and argue about taxes and stuff’ and instead are constructed as highly accessible figures who model hard work and the material successes it can bring. InMichelle Obama, participants see qualities of accessibility and everydayness that both sit alongside and are the source of her influence. Her accessibility is partly framed through her status as a Black woman – this is central to their perception of her as a good leader; one participant describes her as ‘someone who came from a background or was born as a minority, can have that opportunity…I think that makes her be a leader’.

Michelle Obama and Beyoncé can also be seen as occupying the same taxonomic category of ‘leader’ for girls when considered within contexts of digital consumption and reproduction. With the shift away from more traditional forms of news consumption and civic engagement to new forms of online participation, both are figures that girls encounter and share in their social media activities, especially via memes. Rather than providing evidence either that popular culture has the potential to energize the public sphere, or the contrary that those who engage with celebrity cultures are unlikely to engage with politics, the ways in which girls talk about their favourite leaders suggests that they offer a nexus around which ideas about power, influence and gender coalesce and are made accessible for interrogation as well as reproduction. Like Haworth’s ‘Mannequin Defectors’, encounters with the role-model images provoke a consideration of what they stand for.

This project is supported by funding from the Gender and Education Association