GEA are thrilled to have Lucy Rycroft-Smith write this exclusive post on sexism in education for our site.

Lucy Rycroft-Smith is a freelance writer and ex-teacher of ten years. She writes for the Guardian, the TES and various other publications on education, parenting and feminism. She blogs at www.introvertedteacher.co.uk and tweets at @honeypisquared

The children listen intently for their names, sitting up straight grinning nervously in anticipation. A lad’s name is called, and he jumps up, quivering with self-importance. The headteacher extends his hand, and the boy grasps it.

“No!” roars the head. “Not like THAT! Shake my hand like a MAN!”

The boy swallows and pumps his hand up and down in response. I shift uncomfortably in my seat. I know what is coming next. Sure enough, a tall dark girl in my class has her name called and strides gracefully to the front. This time, the criticism is whispered intently, but I catch it.

“Not so hard. You’re a lady. Shake it gently, and smile.”

This is not an isolated case. I’ve heard a PE teacher tell a year 8 boy to “man up” on the sports field. The time when a female teacher tried to join in a friendly playground football match and the male teachers laughed her off the pitch in front of the students. The time I heard colleagues grinning knowingly about a newly qualified teacher being employed “to brighten things up around here”. And the time a headteacher lumped all the “naughty boys” in the year together.

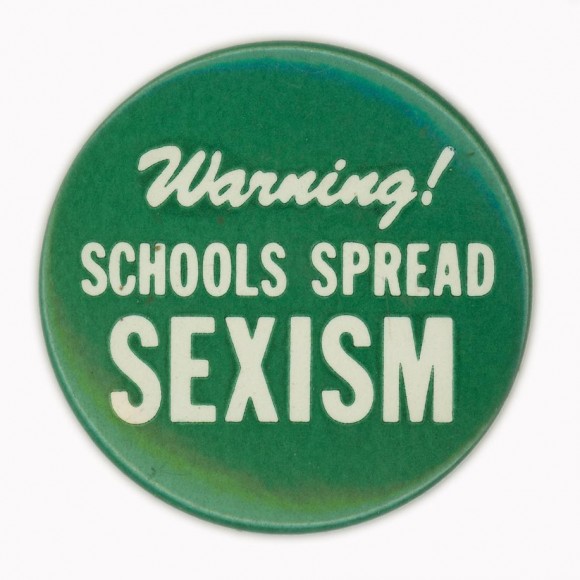

We may not live in an age or a country where overt sexism exists in education, but certainly an undercurrent unconsidered sexism pollutes many of our schools and classrooms. And in my experience, it often goes undetected or unchallenged.

Another example that really shocked me was a staff meeting in another school where we were discussing acceptable uniform. One female child’s parents had asked to be able to wear trousers to school, for religious reasons; the headteacher was reluctant, as it might ‘set a precedent’. I asked if the management team had might consider allowing all the girls to wear trousers, particularly now the weather had turned colder. The headteacher turned to me and explained that he liked ‘girls to look appropriate’, looking pointedly at my own trouser suit. His wife – another teacher at the school – and every other person in the room looked away and said nothing.

Maybe you’re even guilty of it yourself. Have you ever caught yourself saying in surprise “he’s a sensitive boy” or “she’s an aggressive girl”, and considered the underlying assumptions? Have you, hand on heart, marked books with different standards in mind for boys’ and girls’ presentation, because ‘girls are generally neater’? Have you given female toddlers nurse outfits, dolls and play food to cook while keeping the fireman’s outfits, the cars and the dinosaurs for the boys? Then you’re part of the problem.

We live in a world where indirect sexism makes both male and female lives worse in the manner of death by a thousand cuts. Those female toddlers might grow up to be doctors who are continually mistaken for nurses; those male toddlers might want desperately to be ballerinas but feel the intense pressure to join their father’s mechanic business. The Everyday Sexism Project and the #HeforShe Twitter campaign has shown us that assumptions about gender (“The way females dress provokes male behaviour they can’t control”; “Males should always be given the physical, dirty jobs to do”) have a huge impact on people’s behaviour. The last thing our pupils need is those stereotypes being reinforced at school by thoughtless professionals who should know better.

Now is the time to start questioning these ideas. Try not to split your class in terms of gender; there is rarely any need. Distribute menial, physical tasks equally. But more than anything, discuss these issues explicitly with the students. Sexism will affect every single one of them, and they need to be taught the skills to deal with it. Challenge – and encourage pupils to challenge – every incidence you see, no matter how small. Instigate a phrase like “I wonder if you might be making an assumption there that is worth exploring” to promote polite debate.

If you are in SLT or a headteacher, I urge you to explicitly consider your policy on sexism and what it looks like in practice in the classroom, the playground, the staffroom. Have a meeting where you write or edit a formal policy, and use it as a springboard for honest discussion among staff. The excellent Channel 4 programme “The Last Leg” encourages viewers to tweet in about disability issues using the hashtag #isitok; why not have an agenda point on staff meetings where you discuss an ambiguous sexist issue in the same way.

One of the arguments for splitting pupils into gender is for PSHCE lessons. How many females among us have had the ‘period talk’ well away from the boys, while they (presumably) talked about wet dreams and uncomfortable erections? This makes me incredibly sad. There is absolutely no reason why boys shouldn’t understand periods and pregnancy, or girls understand erectile function; in fact the very opposite is true. Even worse, by segregating the sexes in this way we create an enigma and taboo around sexual issues that perpetuates myth and misinformation.

I tried an experiment yesterday. I started a lesson by explaining that the girls in the room needed to pay more attention and listen harder than the boys, because female brains are smaller and we are notoriously worse at maths because it is ‘difficult for us to understand’. No-one batted an eyelid.

The power to influence young minds is ours, and we must acknowledge it can be transmitted in subtle ways as well as direct ones. Encourage everyone to hold the door for everyone else. Stop viewing your pupils through “blue or pink” lenses: their gender is far from the most important thing about them.