By Kate Marston and Claire Thurlow

In the UK, the prominence of a number of anti-trans feminist voices in social and mainstream media has led American journalist Katelyn Burns to term anti-trans ideology as ‘the de facto face of feminism in the UK’ – but this belies a history of feminist and trans entanglements and alliances as well as the continued and resilient support of women for trans people to self-identify their gender. In June, the GEA Executive were amongst tens of thousands of individuals and organisations who wrote to the UK Prime Minister urging the government not to rollback trans rights or disregard the results of the Gender Recognition Act (GRA) consultation. For now, this show of support appears to have prompted the government to affirm that they will not restrict healthcare for young transgender people. Much more needs to be done however to safeguard and build upon existing protections for trans and non-binary people to ensure they can live their lives free of oppression, restriction and violence.

In this blog, we consider how academics and activists can build towards more trans positive futures through exploring some of the fraught yet rich herstories of ‘alliance-oriented trans and feminist politics’. Amid the intensified backlash against trans lives, it has been frustrating to observe the widespread circulation of ill-informed articulations of what feminism is and who constitutes a feminist subject. Dr. D-M Withers notes how so-called ‘gender-critical’ feminists in the UK ‘ventriloquize the building blocks of feminist knowledge upon which they stand, but simultaneously disavow’. Furthermore, Professor Talia Bettcher observes how prominent anti-trans academics fail to ‘display any sensitivity to the existence of a robust literature’ on the relationship between feminism and transgender theory and politics. Arguments against trans rights appear to require feminism to become a parochial single-issue project as opposed to a diverse set of intellectual and activist movements that have long recognised and challenged the complexities of patriarchal power as it intersects with other systems of oppression.

Legacies of anti-trans feminism

A number of feminist scholars have attempted to make sense of the historical legacies of trans exclusionary or anti-trans feminism that has taken particular hold in the UK. While feminist unease with the trans subject had been sporadically highlighted throughout the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM), the foundational anti-trans text was Janice Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire (1979). It remains the most influential text and facets of it can be observed in most anti-trans feminist theorising and activism today. Crucially, Raymond’s book positioned trans identities as a threat to (cis) women. While initially more successful in the US, Dr. Sophie Lewis suggests that it is an import of this strand of US radical feminism that crossed over to the UK in the 1980s. Relatedly, Dr. Withers argues that the theoretical roots of anti-trans feminism in the UK were laid down by the renegade faction of ‘revolutionary feminism’ in the WLM associated with figures such as Sheila Jeffreys. Doubling-down on trans as threat, Jeffries was explicit in her belief in ‘transgenderism’ as a sexual perversion and the promotion of it as a men’s sexual rights movement. In a further attempt to make sense of trans exclusionary sentiment, Dr. Lisa Kalayji looks for the ideological and emotional foundations of anti-trans feminism within divisions over the ‘men question’ in the WLM and efforts to escape the unrelenting misogyny of the radical social movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Others still, trace the anti-trans stance to a continued colonial mentality that relies upon binary classifications and strict category policing (Phipps 2020; see also Lugones 2008). As Al-Kadhi argues, ‘Transphobia has its roots in the systems of colonial supremacy that sought to wipe out gender variance across the globe’.

The struggle for liberation

While the drive to uncover histories of anti-trans feminism offer valuable insights, scholars and activists have also sought to acknowledge the fruitful connections that exist between different struggles for gender justice (Halberstam 2017). Trans and women’s liberation have always been intimately linked by their struggle to escape patriarchal norms. The term gender (as now commonly understood) was developed by feminists from work by psychologists on trans and intersex subjects. Ultimately, women’s and trans liberation are both concerned with equity of rights and life opportunities, freedom from hegemonic gender and sexuality discourses and questions of power. Yet, the women-led social movements that arose during the 1970s have been persistently painted as inherently hostile to trans experiences, despite many trans and feminist scholars having challenged this characterisation.

Withers’ work highlights that the grand narratives ‘invoked within the paywalls of academic feminist theory or the rabid annals of twitter’ rarely do justice to the rich ‘conceptual and lived resources’ produced within the WLM which contributed to contemporary transfeminist discourse. Drawing on archival materials, they illustrate how the emergence of ‘women’s culture’ and women-only spaces was part of the ‘trans-formation of sex’ allowing for intensified experimentation where the ‘female sex was bent into new, irreversible shapes’. Women-only networks facilitated practices such as learning ‘how to fix PA systems, repair faulty car engines, explore the contours of a drum kit, or mend the plumbing’ which expanded the material politics of the female body and what it could do, be and become. Significantly, these spaces and networks were not marked by the same categorical differentiations between cis and trans women that shape contemporary feminist debates. Withers draws attention to testimonial and archival evidence that illustrates the presence of trans activists within the WLM noting, for example, that the keyboardist for the Northern Women’s Liberation Rock Band was a trans woman.

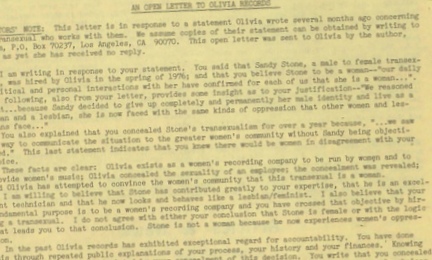

In a special issue on Trans/Feminisms, Stryker and Bettcher (2016) along with Cristan Williams (2016) and Emma Heaney (2016) map the involvement of trans activists in US-based lesbian feminist autonomous organisations in the early ‘70s. They explore, for example, the contributions of the lesbian trans folksinger Beth Elliot, Angela Douglas (the founder of the Transexual Action Organisation) and the trans inclusive politics of the radical feminist lesbian separatist music collective, Olivia Records. In an interview for Vice magazine, former Olivia Records engineer and pioneering trans studies academic Sandy Stone tells her story of living among lesbian separatists in the ‘70s. She details how revelatory it felt to discover ‘that you could be a woman without stereotyping anything, without encountering traditional cis female culture at all’ and travel through a ‘rhizome’ of ‘lesbian safe houses’ from ‘coast to coast and never encounter someone presenting as male, like a wonderful parallel subculture—or superculture.’

When trans exclusionary feminists such as Janice Raymond began threatening and harassing Olivia Records, Stone details that she initially ‘felt really protected by the women of the Collective’. However, the unrelenting nature of the attacks and the risk of boycott action led Stone to leave. Following on from Olivia Records, Stone went on to earn her doctorate with supervision from Donna Haraway and in a faculty comprised of legendary feminist academics such as Angela Davis, Gloria Anzaldua and Teresa De Lauretis. Stone proceeded to publish one of the founding essays in transgender studies, The Empire Strikes Back: A (post)transsexual manifesto.

A place for trans lives in all feminisms

These collective and inclusive herstories question the current common understanding that particular strands of feminism are necessarily trans exclusionary. Furthering the view that there is no inherent need for tension between lesbian feminism and trans-inclusion, and calling for a revival of (a trans-inclusive) lesbian feminism, Sara Ahmed (2017, p. 227) notes: ‘I would suggest that transfeminism today most recalls the militant spirit of lesbian feminism in part because of the insistence that crafting a life is political work’. Ahmed’s assertion that transfeminist texts ‘assemble a politics from what they name’ (ibid), showcases one of the many commonalities between lesbian and trans feminisms. Both lesbians and trans people have been rendered menacing and monstrous killjoy figures within and outside of feminist spaces (see Mitchell and McKinney 2019; Stryker 1994).

Similarly, and contrary to the popular belief that radical feminism and anti-trans feminism are somehow synonymous (not least due to the infamy of the moniker ‘TERF’), radical feminism does not necessitate hostility towards trans people. Catherine McKinnon and Andrea Dworkin, two of the most prominent and celebrated radfems, were both supportive of trans inclusion. In 2015 McKinnon stated “I always thought I don’t care how someone becomes a woman or a man; it does not matter to me. It’s just part of their specificity, their uniqueness like, everyone else’s. Anyone who identifies as a woman, wants to be a woman, is going around being a woman, as far as I’m concerned, is a woman.”

Intersectionality and the category of ‘woman’

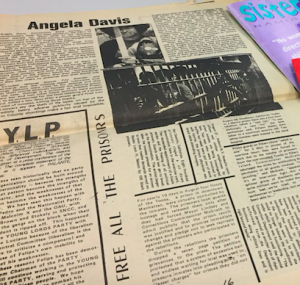

In the aforementioned TSQ special issue, Stryker and Bettcher (2016) also credit the intersectional feminist analyses promulgated by US feminists of color in the 1970s and 1980s with laying the foundation for transfeminist theories and practices. They observe that by raising the question of ‘whether “woman” itself was a sufficient analytical category capable of accounting for the various forms of oppression that women can experience in a sexist society’, Black feminists ‘called for an account of multiple “differences” of embodied personhood along many different but interrelated axes’ (Stryker and Bettcher 2016, p. 8).[1] Transfeminist scholars and activists have not only drawn from the work of Black feminists but also contributed their own intersectional analyses to the fight against racism, state violence and other oppressions (Bettcher 2007). Angela Davis recently credited trans and non-binary communities with contributing to abolitionist feminism by demonstrating that it is possible to imagine more socially just worlds that challenge ‘that which is totally accepted as normal’.

Black feminist and trans scholars have also explored the historical imbrication and interplay between Blackness and transness (Riley Snorton 2017; Bey 2017; Sharpe 2016). Marquis Bey (2018, p. 165) illustrates that the ‘subjective nexus of Black and woman, for example, irrespective of an identified trans gender, also experiences the surveillance and invasion of their bodies going through airport security (e.g hair searches), expulsion from bathrooms, housing discrimination and historical invalidation of their womanhood’. Scholars including Lola Olufemi (2020) and Alison Phipps (2020) have noted the ‘whiteness’ of the UK anti-trans feminist movement. Phipps further suggesting the paucity of British intersectional analysis, relative to the US work noted above, as a contributing factor to the prominence of ‘gender critical’ views in the UK. Dr. Gail Lewis observes how Black women’s work in Britain was denied credibility and respect by white feminists as they entered the Academy and formed women’s studies networks and reading lists.

Continuing to learn from one another

Given the marginalisation of Black British feminist thought within the Academy, it is important to re-visit and learn from the Black and working class women-centred social movements, such as Wages for Housework and the Black Women’s Movement, that thrived alongside the predominantly White and middle class WLM in 1970s Britain. Significantly, these movements did not share the same unease with trans subjectivity as expressed by minority factions of the WLM. Lewis, who was a co-founder of the Organisation for Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD) and member of the Brixton Black Women’s Group, highlights that the Black Women’s Movement always questioned limited articulations of gender and notes her surprise at those who have been so troubled by trans* politics. The Black Women’s Movement and Wages for Housework were characterised by coalitional working between contingently autonomous groups, activating ‘an organizational tactic to mobilize across and beyond existing racial, gender, sexual, and class configurations while recognizing the irreducible differences’ (Capper and Austin 2018, p. 449). Wages for Housework, for example, was an international movement comprised of autonomous groups such as Black Women for Wages for Housework, Wages Due Lesbians (now Queer Strike) and the English Collective of Prostitutes.

Transfeminist scholars and activists have turned to the organisational tactics and theoretical interventions of these Black and working class women-centred social movements for inspiration. Dr. Nat Raha, for example, observes how the Wages Due Lesbians campaign provided important insights into queer social reproduction by challenging the heteronormativity within Marxist feminist conceptualisations of unwaged domestic labour. Unlike the lesbian separatist movements referenced earlier, the largely Canadian / UK-based Wages Due campaign did not advance lesbianism as necessarily liberatory in itself. Instead, they noted how economic power continued to shape and limit women’s sexual choices (Caper and Austin 2018, p. 449). Raha draws on the work of Wages Due in order to advance a radical transfeminism and highlight the limits of trans liberalism. Rather than focusing on securing a particular ‘packet of entitlements’ and rights for trans people, a radical transfeminist agenda explores possibilities for common struggle across the intersecting issues of precarious working conditions, transmisogyny and sexism, white supremacy, ableism and sex work. Raha looks to contemporay and historical queer and trans-focused mutual aid support as a strategy for survival and world-building.

Conclusion

We are undoubtably living through a moment where trans lives are subject to unwarranted scrutiny and conjecture; where the historical imagining of trans as threat has reemerged and rejuvenated. That this image is often promoted by a small section of women from within the feminist movement remains disappointing. However, in the prevailing social and traditional media narrative it is easy to overlook the uplifting herstory of trans-feminist alliances which have been integral to the women’s liberation movement and which continue to inform and enrich our understandings; it is easy to overlook the collective struggles endured and the support and solidarity enjoyed. Scholars and activists demonstrate that it is in feminisms’ recognition of difference and shared experience that it is at its most sophisticated and demanding. At its best feminism is a movement that understands its role as a collective liberator of the margnalised and resists being reduced to a parochial border guard preoccupied with reserving womanhood for a privileged few.

Bio

Claire Thurlow is a PhD candidate in the School of Law and Politics at Cardiff University. Her current research looks at contemporary feminist reactions to trans identities in the UK. Her wider research interests concern the intersections and divergences of feminism, queerness and LGBTQ. She is a white cis-gender queer whose pronouns are she/her.

Kate Marston is a PhD candidate in the School of Social Sciences at Cardiff University. Her research draws on feminist posthuman and new materialist theories to explore young people’s digital sexual cultures through creative, visual and arts-based methods. She is a white middle-class genderqueer lesbian whose pronouns are she/they.

References

Ahmed, S. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Bettcher, T. 2007. Evil deceivers and make-believers: Transphobic violence and the politics of illusion Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 22 (3), pp. 43–65.

Bey, M. 2018. “Other Ways to Be: Trans.” Women and Language 41(1), pp. 165 – 167.

Bey, M. 2017. “The Trans*-Ness of Blackness, the Blackness of Trans*-Ness.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 4(2), pp. 275 – 295.

Capper, B. and Austin, A. 2018. “Wages for housework means wages against heterosexuality”: On the Archives of Black Women for Wages for Housework and Wages Due Lesbians. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 24(4), pp. 445 – 466.

Halberstam, J. 2017. Trans: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Heaney, E. 2016. Women-Identified Women: Trans Women in 1970s Lesbian Feminist Organising TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 3(1-2), pp. 137 – 145.

Lugones, M. 2016. The Coloniality of Gender in Harcourt, W. (Eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development: Critical Engagements in Feminist Theory and Practice London: Palgrave Macmillan

Mitchell, A. and McKinney, C. 2019. Inside Killjoy’s Kastle: Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and Other Lesbian Hauntings. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Olufemi, L. 2020. Feminism Interrupted: Disrupting power. London: Pluto Press

Phipps, A. 2020a. Me, Not You: The trouble with mainstream feminism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Phipps, A. 2020b. Transphobia, whorephobia and (as) capitalist-colonial gender Manchester: Manchester University Press

Raymond, J. 1979. The transsexual empire: The making of the she-male. Boston: Beacon Press.

Riley Snorton, C. 2017. Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sharpe, C. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press.

Stryker, S. 2004. Transgender Studies: Queer Theory’s Evil Twin. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 10(2), pp. 212-215.

Stryker, S. and Bettcher, T. 2016. Introduction: Trans/Feminisms TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 3(1-2), pp. 5 – 14.

Williams,

C. 2016. Radical Inclusion: Recounting the Trans Inclusive History of Radical

Feminism TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly

3(1-2), pp. 254 – 258.