Emilie Lawrence and Jessica Ringrose

From toilet rolls to sex toys, 50 Shades of Grey spin-offs show that the support for the trilogy has been huge and the backlash even bigger. The book has been criticised for romanticising domestic violence, mental health issues, and for its childish repertoire of words used to describe body parts, experiences and sex. But the pressing question about the enormous success of the book trilogy and now the first instalment of the movie is why now?

Why during a period of proclaimed postfeminist equality for women and girls in education, work, and the public sphere do we see the fetishisation of a narrative of masculine sexual dominance and feminine sexual pathology being writ large in the popular cultural imagination? Also critical for an educational audience are pedagogical questions about what type of fantasies does 50 Shades sell to women and girls? Given widely documented panics over the sexualisation of children and girls – and the questions of gender equity and ongoing sexual double standardsraised in debates on the impacts of sexualisation of femininity on girls’ self esteem – are texts that normalise male sexual dominance seen simply as playful fun? How can we engage in a meaningful discussion of these issues with young people?

Interestingly, 50 Shades of Grey emerged from Twilight fanfiction. This explains the similarities both in writing style and reliance on staid and limiting gender roles. There is a myriad of cross-referencing and inter-textual referencing at play; for instance, in Twilight we see Bella presented as a shy, clumsy teen caught in a love triangle between an emotionally abusive werewolf and an emotionally abusive vampire (Gee, the choices open to teen girls nowadays…) Then in 50 Shades we have Ana similarly depicted as a shy, socially awkward young woman. Both authors emphasise the fragility and naivety of the female leads, paying attention, and lending support to how ‘necessary’ the role of the male lead is in keeping them safe.

What is interesting is how the construction of the relationship between Bella and Edward in Twilight and Anastasia and Christian in 50 Shades rely on very stereotypical notions of male sexual desire as hardwired aggression, with girls and women the passive objects of prey. The gendered and sexual relationships presented in both the Twilight and 50 Shades are worrying at best, dangerous at worst. The authors also draw on notions of vulnerability, sexual innocence and yet being up for whatever the man desires as the ideal version of sexual desirability and‘sexy femininity’.

The primary focus of the female characters is to not only be sexually appealing but sexually innocent. These tropes are very interesting in relation to sex and relationship education in school, which have been critiqued internationally as leaving girls’ sexual desires and pleasure largely absent from most of the curriculum. Sex education is widely critiqued as foregrounding boys ‘parts’ (through use of condoms on erect penis for instance) and suggests implicitly and explicitly that male sex drives are to be managed by girls in appropriate ways to promote sexual health and virginity. Books like 50 Shades and Twilight perpetuate the idea that awoman’s worth is somehow inextricably linked to the state of her hymen and wide-spread purity myths. Anastasia is desirable because she has never had sex; Christian is desirable because he has.

50 Shades presents Anastasia as passive, naïve and sexually insatiable once Christian opens her eyes to the world of sex. Naturally she entered the relationship a virgin whilst he came to the bed of pain a gifted lover. This further reinforces the double standards around male ‘players’ and female ‘slut shaming’ that are so pervasive in society in relation to female sexuality. Broadly speaking women are expected to be sexy but not sexual; sexually active women run the wrath of being morally condemned for sexual activity whereas sexually active men are able to maintain both a moral high ground and ‘legend, top lad’ status. This plays out in very interesting ways in relation to the contemporary problems with lad culture and rape culture we are seeing in schools.

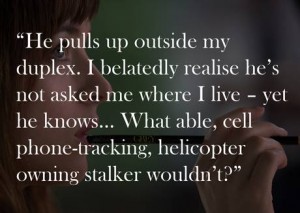

50 Shades presents a heady account of one man’s sense of entitlement and the unpaid, unappreciated emotional labour performed by Anastasia. She is constantly checking herself throughout the books; wary of upsetting, angering or confusing Christian. She is reluctant to open up or be honest with him because she ‘knows what he is like’ and at one point.

Anastasia breaks down at several points in the story, crying and blaming herself for Christian’s inability to love her the way she wants to be loved. This victim blaming response has again been widely critiqued in legal and criminological debates, as neglecting attention to gendered power dynamics and debates around sexual consent. Anastasia justifies his aggressive behaviour, brushing it off as the result of a bad childhood (which coincidentally involved being abused by a powerful woman). She also makes repeated allowances because she has never had a relationship before. She is isolated from her friends and family; add or change a few words and you have a crime report on domestic violence in your hands – all under the romantic guise of wanting to keep her safe and loving her so much.

In Twilight and 50 Shades, the relationships the women have with the men in their lives are presented as paramount but also literally integral to their bodily survival. Girls and women are presented as incomplete if they are not sexually desired (and loved) by men. Men are the granters of esteem to women in a classic binary of male superiority and human-ness against which women and girls are measured and dependent, particularly in relation to desire.

Without the affections of the male Bella and Ana literally fall apart when their relationships break down; both stop eating. This aspect of bodily breakdown is significant. The internalisation and self-punishment through bodily control in the face of male rejection echoes psychological notions of women’s internalisation and pathologization of aggression. Women are unable to cope rationally with aggression therefore they internalise and self-destruct. Endorsing and legitimating this narrative is relevant in relation to debates that naturalise female passive aggressive behaviour as well as debates on anorexia and self-harming. By shrinking themselves into insignificance and further infantilising themselves the narratives play into a story of male power and heroism, which relies on an idea of male saviours, duty bound to swoop in and ‘save’ girls and women. Anastasia regularly refers to how empty she feels, how she is unable to manage to eat and on reuniting with Christian, this is the first thing he notices. Instantly angry with her he forces her to eat; thus asserting his position as dominant and in control. This echoes discourses around eating disorders in ways that celebrate rather than question body shaming and body harming practices.

If we think of the books as sex education writ large in popular culture, there is a worry that they will leave girls and boys and men and women feeling inadequate about their sexual experiences; men will think it is as easy as providing a quick fumble and nipple bite to please a women, whereas girls might worry that there is something wrong with them if it takes them longer than thirty seconds to be in the mood and in a position where they can orgasm.

Feminist critiques argue that mainstream pornography neglects attention to the mechanics of arousal for women, focusing instead on fulfilling masculine fantasies for quick ejaculation. In the same way, the sex depicted in 50 Shades is unable to open up avenues for ordinary sexual play for women. Perhaps a fantasy of being suspended from the ceiling for a spanking twice a day does provide a potent if perhaps ridiculous fantasy for some, and maybe some of 50 Shades is partly innocent play and fun. kindprotect But the story lines that legitimize the sexual pathologization of women and celebrate male sexual and economic dominance, mean that, as feminists, we have much to do. We need to keep opening up debate and discussion about forms of femininity that do not subsume questions of feminine pleasure, desire and fantasy to the role of sexually and emotionally servicing men.